Elder Qualifications (1 of 3): The Big Picture

The following is the first in a series of blogs regarding the biblical qualifications for eldership. This blog examines the overall purpose of the qualifications, the other two blogs relate to specific qualifications that merit special attention.What makes someone fit to lead?

Who is fit to lead in Christ’s church? Over centuries of church history, that question has generated a lot of debate. For our Roman Catholic friends, the issue is supposedly settled by apostolic succession. They claim a direct line from the Apostle Peter to the current Pope, so deciding who is in charge is relatively straightforward. For those in the Plymouth Brethren Church, the idea of leadership itself is problematic: they refuse to ordain anyone to the clergy, arguing that all Christians ought to share equal authority. Between these two ends of the spectrum, church history has produced a wide variety of approaches to church leadership.

But what does the Bible say? The shortest answer to that question can be found in Acts 20:28, where Paul addresses the Ephesian elders and says “the Holy Spirit has made you overseers.”¹ Ultimately, God decides who is given leadership in his church. But the Bible has more to say than just that. God has also given us the qualifications for the job. In this way, he uses us to put his leaders in place.

Every job has qualification requirements. Those might include a certain level of education, physical abilities, experience in the field, or any number of other things. My first job was as a scoreboard operator for little-league football games. I don’t remember what requirements were on the hiring form, but I expect they included things like: “Must have a basic knowledge of football’s scoring system” and “Must be able to do mental-math in a timely manner.” If I couldn’t meet those qualifications, I couldn’t do the job. So, what are the qualifications for a pastor? In two of his letters, the Apostle Paul gives us a direct answer to that question:

An overseer must be above reproach, the husband of one wife, sober-minded, self-controlled, respectable, hospitable, able to teach, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, not a lover of money. He must manage his own household well, with all dignity keeping his children submissive, for if someone does not know how to manage his own household, how will he care for God’s church? He must not be a recent convert, or he may become puffed up with conceit and fall into the condemnation of the devil. Moreover, he must be well thought of by outsiders, so that he may not fall into disgrace, into a snare of the devil. (1 Timothy 3:2-7)

If anyone is above reproach, the husband of one wife, and his children are believers and not open to the charge of debauchery or insubordination. For an overseer, as God’s steward, must be above reproach. He must not be arrogant or quick-tempered or a drunkard or violent or greedy for gain, but hospitable, a lover of good, self-controlled, upright, holy, and disciplined. He must hold firm to the trustworthy word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine and also to rebuke those who contradict it. (Titus 1:6-9)

The same Holy Spirit who installed the Ephesian elders of Acts 20 also inspired Paul’s words in 1 Timothy 3 and Titus 1. God makes a man a pastor, but he uses us to do it. He’s given us the qualifications so that we know we’re installing a man God thinks is right for the job.

For the remainder of this blog, we’re going to take a look at the qualifications themselves. We’ll do a big-picture overview here and the next two blogs will focus on specific qualifications that merit more attention. Our primary concern now is to understand Paul’s main point: what is he doing in the elder-qualification passages as a whole?

A Brief Word on Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics is the study of how meaning is communicated. You may not realize it, but you engage in hermeneutics all the time. When you read poetry, you suspend your expectation of strict literalism and willingly roam in a world of imaginative metaphors and vibrant imagery. But when you pick up a scientific textbook, you demand concrete literalism. Each of those is a hermeneutical posture. You and the author have a relationship predicated on your shared assumption about the kind of literature he’s giving you. Imagine the chaos when that relationship is confused: reading a poem as if it’s data analysis, or vice versa. The communication of a text’s meaning requires the author and the reader to be on the same page (no pun intended).

The reader’s first job, then, is to understand what kind of literature the author has written. Fortunately, this is usually easy: she simply needs to read it and recognize the clues found in the text itself. If he’s listing measurements of flour and baking soda, she needs to get out her cooking utensils because this is a recipe. If he’s telling individuals to exit stage-left after delivering their lines, she needs to prepare the stage because this is a play.

So, if we want to rightly understand the elder qualifications, our first job is to get on the same page as Paul. Whatever he’s saying to us, we first need to recognize what it is in order to understand what it means. We need the right hermeneutical posture.

The Elder Qualifications are a Virtue List

When we look at Paul’s two lists (1 Timothy 3:2-7 and Titus 1:6-9) we see immediately what they are: a virtue list. With one notable exception (see below), every quality Paul mentions in 1 Timothy 3 and Titus 1 can be categorized as a character virtue. A man who avoids drunkenness, handles money wisely, manages his home well, exhibits humility, and has a respectable reputation is a virtuous man. In short: elders must be men of upstanding character. That’s Paul’s main point.

This initial observation is absolutely crucial. While the world may prioritize unique talent, superior intelligence, entrepreneurial creativity, and proven results in its leaders, such qualities fail to merit a mention in Paul’s lists. As God told the prophet Samuel, “Do not look on his appearance or on the height of his stature…For the Lord sees not as man sees: man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart” (1 Sam. 16:7). Instead of charisma, God requires character. He wants maturity, not managerial skills. Godliness more than giftedness.

There’s also something very normal about these qualifications. As one theologian notes, “the list is remarkable for being unremarkable.”² Godly character is something to which every Christian should aspire–not just pastors! In fact, almost all of these qualities can be found elsewhere in the Bible as a command to all Christians. The pastorate is not for some super-class of mega-Christians who float over the floor while praying. It’s for those who are doing what every Christian should be doing.

Paul’s emphasis on character gives clarity to the subjectiveness of many of the qualifications as well. How recent is “not a recent convert”? Two years? Ten? How often does a man have to practice hospitality to qualify as “hospitable”? Paul doesn’t get bogged down in such details because making a hard rule isn’t the point–godliness is.

Pastors aren’t required to be exceptional (brilliant minds wielded through charismatic personalities or faultless Christians with an immaculate pedigree), they’re required to be exemplary (godly men worth imitating). This is why Peter commands pastors to “be examples to the flock” (1 Pet. 5:3) and the author of Hebrew tells church members “Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God. Consider the outcome of their way of life, and imitate their faith” (Heb. 13:7). If an elder is to be an example worth imitating, his personal piety is paramount.

The one qualification that should be seen as an exception to the overall focus on character is “able to teach” (1 Tim. 3:2; cf. Tit. 1:9). This makes sense as an exception because it’s a unique aspect of the job. Pastoring requires teaching! This crops up in the Hebrews passage just quoted: elders are “those who spoke to you the Word of God” (Heb. 13:7). Sometimes that’s preaching behind a pulpit, sometimes it’s opening the Bible with a struggling member at Starbucks, but the job of an elder requires verbally communicating the truths of the Scriptures in such a way that people understand and learn. They must be able to teach.

While essential to the job, the ability to teach the Bible is not sufficient for eldership by itself. Church history has sadly shown that a gifted communicator who lacks holiness does not make for a good pastor. Members learn from what a pastor says and what his life shows. But when a teaching gift is wielded through mature Christian character, the church has found a qualified elder.

Is This Everything?

We must now ask an important question that will guide our hermeneutical approach in the following blogs: is this everything? In other words, how exhaustive are these lists? Is Paul listing all the qualifications for the job? You might notice that Paul never says an elder must be “a man of prayer.” So, is it ok to make someone an elder who never prays?

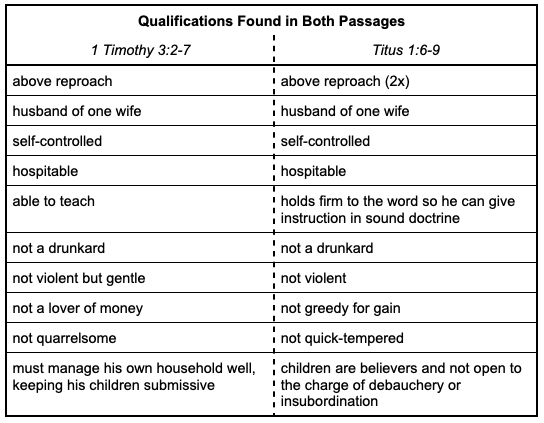

We can answer this question by comparing the two lists Paul writes. When we do that, we find that Paul includes many of the same qualifications in his letter to Titus as he did to Timothy. We also see, however, that the lists are not identical. The following chart lists the qualifications that appear in both passages.

Around 70% of the qualifications are repeated in both lists. Several are verbatim, but sometimes Paul expands or paraphrases an analogous idea. For example, he says “not a lover of money” in 1 Timothy but “not greedy for gain” in Titus. The basic idea is the same but each has a slightly different emphasis. He says “able to teach” in 1 Timothy but “holds firm to the word so he can give instruction in sound doctrine” in Titus. Again, the concepts are comparable, but not quite identical.

There are, however, several qualifications that are unique to each list. These are shown in the following chart.

Here we find that Paul did not give his two pastoral protégés the same list of qualifications. That’s significant. Timothy and Titus pastored in vastly different contexts, hundreds of miles apart (Timothy in Ephesus, Titus on the island of Crete). They weren’t able to “compare notes” on elder qualifications. The fact that the lists are not identical indicates that neither list was meant to be exhaustive. Paul is not listing every quality that must characterize an elder nor is he being absolutist about the qualifications he includes. For example, Paul tells Timothy that an elder “must not be a recent convert,” but he makes no such demand of Titus. Does that mean Paul considers that qualification less important? I don’t think so. In fact, I’m confident that Titus would not have made a recent convert into an elder–even though his letter from Paul made no mention of that consideration. Why? Because the elder qualifications are a virtue list. They describe mature Christian character and a recent convert would not have such character. Godliness is a product of years walking in step with the Spirit, so a recent convert necessarily lacks that Spirit-wrought sanctification. In both 1 Timothy and Titus, Paul describes the big-picture requirements (character and an ability to teach) so clearly that Paul doesn’t have to provide identical lists.

Why doesn’t Paul mention that an elder must be “a man of prayer”? Because he doesn’t have to. Both lists describe godliness in general terms, and obviously godly character includes a robust prayer life.

The elder qualifications are a recipe of righteousness. Paul is saying “these are the kinds of ingredients that make for a godly man, a man fit for eldership.” Elders must be high-character men who are also able to teach. That’s the biblical qualifications in sum.

The Question of Timing

One important question remains: timing. It may sound odd, but we must also consider when Paul is requiring an elder to be godly. Certainly for the duration of his eldership(!), but are we meant to look back on a man’s entire life or focus on the man in front of us now?

The first approach we may liken to a car history report. When you purchase a vehicle, you typically get a report of all the problems the car has experienced in the past: accidents, repairs, water damage, etc. The report tells you if the car has significant problems in its past. Some would argue that that’s what Paul is doing in the elder-qualification lists. His intention, they say, is to provide a life-history resumé. He is listing specific situations and sins from a man’s personal history that, if breached, would disqualify him permanently.

We may liken the second approach to your vehicle’s annual inspection. Every year, to renew your registration, you take your car to a mechanic to run a series of tests. Do the blinkers work? Do the tires have good tread? Are the brakes functioning properly? The car’s history is not irrelevant to these tests–it may have been in an accident that created lingering problems–but the focus is on the present. This report tells you if this is the kind of car you should be driving now.

This second approach is far more like what Paul is doing in the elder-qualification lists. We know that because some of the first pastors in the Bible had abysmal life-history resumés. Peter identifies himself as “a fellow elder” (1 Pet. 1:5), despite the fact that Jesus once rebuked him for being a mouthpiece of Satan and Paul “opposed him to his face” for anti-gospel conduct (cf. Gal. 2:11-14). The Bible is filled with similar examples of ugly sins from men who would be godly leaders (Paul, David, James, John, etc.). But godliness is a process. Peter’s own trajectory proves that. Thus, to demand a specific life-history from an elder candidate runs the danger of graceless legalism.

The only qualification that could be taken to refer to a uniquely-disqualifying sin from a man’s past is “husband of one wife.” If so, it would certainly be an outlier. However, as we’ll see in the next blog, this qualification does not prohibit divorced men from serving as elders, as some take it to mean.

Paul’s focus is on a potential elder’s current character. This doesn’t deny the relevancy of an elder candidate’s pre-history. Rather, it subordinates that pre-history to the present reality. For example, if a man being considered for eldership has at some point in his life been a drunkard, then his past abuse of alcohol is certainly relevant to the question of his qualification. It matters, but it lacks the power to necessarily disqualify him. It is possible that his drunkenness is so far in the past that it is no longer considered a defining aspect of his character.

What makes someone fit to lead? (revisited)

We began with a simple question: what makes someone fit to lead? Secular corporations, political parties, and other groups will all have their own answers to such a question: a leader must be dynamic, exciting, and capable. Many Christians will also presume an answer: some may “raise the bar” as high as possible to preserve the sanctity of the office, while others may downplay the qualifications to “get their guy.” But neither of these options is faithful.

Churches don’t get to invent their own criteria for leadership–they come to the Bible for it. In the end a church’s elders must have godly character and be able to teach. No amount of skill or knowledge can make up for a man lacking in godliness. But a man of Christian maturity–with a sufficient knowledge of the Scriptures and the capacity to communicate them–is a man the Holy Spirit makes an overseer (Acts 20:28).

¹Acts 20 uses the terms “elder” (presbyteros), “overseer” (episkopos), and “pastor” (poimēn) to refer to the same group of men. For this reason, it’s clear that all of these titles are used interchangeably to refer to the same leadership office.

²D.A. Carson, “Defining Elders”, January 4th 1999. https://www.9marks.org/article/defining-elders-2/